nor (b. 1993, Singapore) is an artist whose works investigate the performative aspects of our identities. Her work is rooted in self-portraiture, exploring themes such as gender, sexuality and ethnicity through photography, film and performance.

Her latest exhibition, In Love, was on show at the independent art space, Coda Culture, for a week. We caught up with the artist whilst she was in the midst of deinstalling the work. She pulled out her copy of Larry Sultan's book, Pictures From Home, and whilst flipping through the publication, we started chatting about her own practice and how In Love came about.

Her latest exhibition, In Love, was on show at the independent art space, Coda Culture, for a week. We caught up with the artist whilst she was in the midst of deinstalling the work. She pulled out her copy of Larry Sultan's book, Pictures From Home, and whilst flipping through the publication, we started chatting about her own practice and how In Love came about.

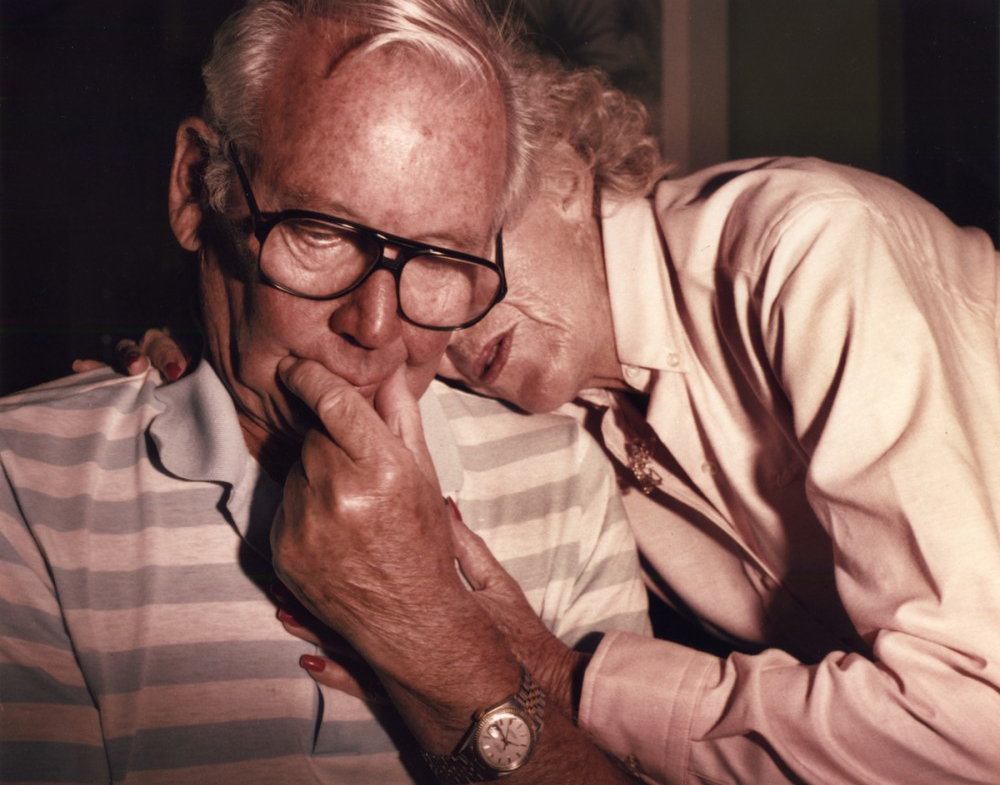

¹ Conversation on Bed, Larry Sultan

1986

² Close Up, Larry Sultan

1992

Let's start with Larry's works. Why were you drawing to choosing his works for this particular interview?

Back in 2017, I was taking a class with Alecia Neo, who's an amazing photographer and somebody I really respect. She taught a class on the narrative portrait. The class would usually begin at 4:30pm and go on until 7:30pm, but sometimes the class stretched on until 8pm or even 8:30pm. This would have been after a really packed day. I would have gone for Spanish in the morning and lighting class for three hours before even coming to [Alecia's] lesson. So, I would always go into her class emotional. I would come in feeling like, ugh, I've had such a long day, and just I want to go home.

During one of these classes, she showed us Larry Sultan's works. That week, the theme of the lesson explored photographing the family, home and its space. There was one particular image within this collection that really got me, and it's this one, Close Up. When Alecia presented it, I thought to myself, "Oh my God — I'm so emotional". I think what interested me about his body of work was the fact that there was no way in the world that these photographs were snapshots. They're really staged, and Sultan was paying attention to light and colour. I feel like he might have even dressed [his parents] up, because some of these portraits could work as fashion editorials. I think with the body language of his subjects — his intention might not have been to capture them this way, but as the project expanded, Sultan probably started realising that that was the strength of this body of work. [In the publication,] he also included some stills of family videos. It's so strange, because when I saw this photograph, I felt such an intense sense of loneliness. I immediately thought of Nicolas [Ow], who would later on become my collaborator [for In Love].

At that point in time, Nicolas and I were just friends. It's very strange because there was tension between Nick and myself. The semester before, he tried to write a queer narrative and I just felt like it was weird. I didn't like it, and I was very harsh about it. With regard to my own activism, and speaking as a queer person, I do get very unapologetic about such things. That kind of strained our relationship. So when I saw this image, I thought of Nick and I missed him. I wasn't romantically attracted to him. It was just that from the get go, I've always associated Nicolas with a sense of familiarity and home. For some reason, he reminds me of my grandfather. It became the starting point for us to begin talking to each other again. Although In Love hadn't been conceived yet, I think this laid the foundations for it.

With regards to the other works I picked out — Momo Okabe's and Pixy Yujin Liao's works — I found their works through an article on Dazed and Confused. They do themes, right, and there was one on the theme of love. I only looked into their works because they were Asian artists, and Okabe turned out to be a queer artist herself. That really drew me into those works.

I've known about Marina Abramović and Ulay since I was eighteen. There's a lot of romanticisation surrounding their collaboration and what they have. But it's also quite frustrating because it's like, aiyah, you love each other, just say lah! It's so dramatic, you know? Like going from each end of the [Great Wall of China] then walking towards each other.

These were the bodies of works that informed me at different stages [of In Love]. The works of Sultan, Okabe and Ren Hang were important to the early stages of In Love. Abramović and Ulay's influence was really strong on the second half of the project.

³ It's Never Been Easy to Carry You, Pixy Yujin Liao

2007 — Present

⁴ The King Under Me, Pixy Yujin Liao

2007 — Present

Between these artworks you chose to talk about for this interview and In Love, I saw them all being permutations about similar themes.

Sultan's and Okabe's works, in particular, are incredibly poignant. They both don't censor or shut out moments that would otherwise seem too mundane.

In Love touches on these incredibly personal moments too. Coming into the space feels intrusive, as if I'm walking into someone's bedroom. Why was it important for you to portray a relationship in such an emotionally charged manner, and how did you and your collaborator decide which moments would be photographed and included in the project?

Both my collaborator and I had not been in romantic relationships prior to the project, so we were both navigating love as a construct in a very naïve way. Prior to In Love, I set up a Tumblr site where I would ask my friends, or just anyone who came across the site, to submit their thoughts on what love was. From there, we then picked out what we wanted to explore. The narrative started out when we were in the bedroom. That was the first shoot. I thought it was just going to be one shoot, and we would be done with the project.

We both created characters — nor, I mean now I go as nor, but previously it was just a character, and Junjie, which was a play on his Chinese name. Whilst I was getting made up, we were both trying to create these characters and a narrative that would go along. The first narrative explored the idea of reconciliation between nor and Junjie. In the story, nor was changing into this whole other person, and though Junjie was aware of these changes, he could not accept it. This was something we wanted to pick apart with regards to the concept of love.

The entire idea of love is incredibly romanticised, but there's always a point of conflict that can either make of break the relationship. We really wanted to start with that.

The main idea for this make or break moment was nor’s gender identity, and how Junjie and nor would navigate through that. From there, we worked backwards with regards to timeline. From that moment of conflict and reconciliation, we worked towards the honeymoon period.

After that, people were saying, you know, "We don't care about nor and Junjie, we want Nick and Dyan". That was back then when I used to go as Dyan. From there, the normal and the everyday became very important. Because the queer aspect of nor and Junjie's relationship aside, we wanted to see how we could create an experience that others could relate to. We found that it was really in the small things — like going on dates to the Singapore Art Museum, eating char kway teow at Seah Im, or going for a night swim at Labrador Park. Those were the sort of things that we wanted to explore. The everyday, mundane experience is something that ties queer and non-queer relationships together.

The first series of images were very queer-specific, so some thought that they were hyper sexualised, because they were. They were hyper sexualised. But we wanted to see how we could move forward from there. How could we create images that other people could relate to? That was the thought process behind the importance of the everyday images in In Love.

⁵ Untitled, Momo Okabe

Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam, 2013

How did the Tumblr submissions help with the sort of narratives you both put together for the characters?

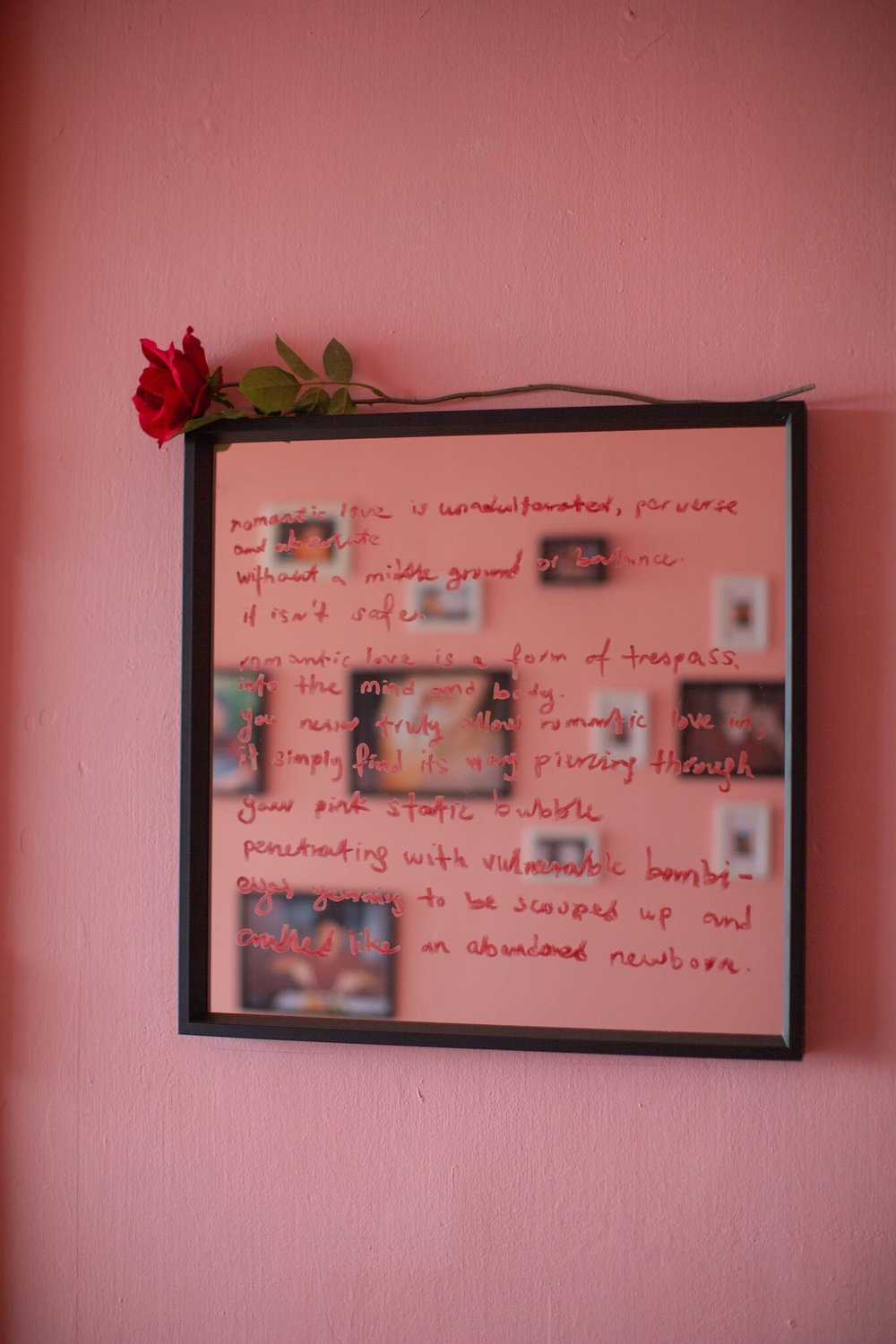

There were some really intense submissions where that were a little too personal to be included. But we also received poetry submissions, and I wrote one of them on the mirror for the exhibition. We picked out what was applicable to the idea of young love, and translated it into our own shoot sessions.

⁶ Breathing In, Breathing Out, Marina Abramović and Ulay

1977

Another thing that struck me about Abramović and Ulay's Breathing In, Breathing Out was how the two artists were performing the concept of love. As we've just discussed, love is something that's so incredibly personal. Yet performance, on the other hand, almost sits on the opposite end of the spectrum to that. How did you navigate the performance of something as intimate as love?

As I mentioned earlier, the collaborations between Abramović and Ulay are frustrating, but they have been incredibly romanticised. What pulled me into their collaborative works was how they spoke about the effect one person had on the other, and the extent to which this effect could be felt.

Initially, Nicolas and I had characters, but by the second half of In Love, people were no longer interested in the characters. People wanted to know about Nicolas and I. With that framework of how Abramović and Ulay affected one another, I became shutting down emotions relating to how my collaborator would make me feel. It wasn't the easiest thing. I felt that if I was no longer able to process my emotions clearly or no longer able to take a step back from the situation, there would have been moments where I'd think to myself, holy shit, I'm in love. The scariest thing was that if that had happened, that would have compromised the initial message of the narrative we both created, and it could even jeopardise my friendship with Nick. I think that was the scariest thing.

Breathing In, Breathing Out really affected me because the two artists were just breathing in and out of each other until they both passed out. I think it was the idea that one person could be so vulnerable around another. With Nicolas, I feel so vulnerable. From the get go, he feels like home. Then there was the tension, and us trying to reconnect through this project. Even getting to know him felt like another religious or spiritual experience in and of itself. So this was one person that I felt incredibly vulnerable around. If at any point in time I lost control over myself, he would have had total power over me. That framework really borrowed from the collaborations between Abramović and Ulay.

You spoke about how the message of the project could have been compromised in the event that you were unable to compartmentalise. Did the message of the project shift as time went on? How did the collaboration feed into that?

Both of us were never involved in romantic relationships before, so we would go on dates then ask ourselves, so, is this what couples do? Nick is a film maker, and prior to university, I was a film student myself. So there were a lot of moments where we found ourselves doing character building and world building. But at the same time, it was difficult to play or act out a character that hadn't been fully developed yet.

A lot of it was about getting to know each other — our own personal stories, and choosing which aspects of that we could insert into our characters. I had the opportunity of getting to know how he was raised, about his family background, his Mum, his Dad, and where they had all come from. He also told me about his first memory. It came to a point where I felt an urgent need to see a photograph of him as a baby. I wanted to see if the essence or the spirit of a person could be located in a photograph of them as a child. After seeing a photograph of him as a baby, I definitely felt it was. He had this huge grin on his face as a baby. It's just one fragment of time captured there, but the moment lives on until this day. For me, as a baby, I always looked sad. I think these were aspects of ourselves that we really tried to fit into our characters. Because we had to get to know each other through such intimate sharing sessions, it really made us feel very vulnerable around each other. That was something that I didn't really realise myself until my tutor pointed out that we were both putting in so much of each other into the project that we didn't have to really play characters. There was already enough of a draw for the viewer, so my tutor thought that we could maybe explore the second half of the project with that in mind.

Initially, I wanted to keep these intimate experiences to myself. I wondered what I could present that would still capture the essence of vulnerability, without inserting too much of myself or himself. My lack of willingness to share everything really came through in the exhibition space. A lot of people would come out of seeing the show and start sharing the life stories with me, and I would be like, what? No! I'm not emotionally equipped to do this!

But a lot of people came out of the space feeling vulnerable, so that really was the theme that resonated most with viewers. It wasn't queerness, or the idea of romantic love as performative — but it was how being around another person can make you feel.

Viewers felt like In Love was able to bring out that particular aspect, so they'd come out of the space wanting to share a part of themselves with someone else.

⁸ Untitled, Ren Hang

2015

Starting out, were you interested in exploring how people would respond to In Love especially in relation to the notion of vulnerability?

It only came out during the second half of the project. I created In Love out of a narcissistic desire to see transgender girls, like myself, or more specifically, brown, transgender girls. Queer art, or the queer narrative through art in Singapore, is present. But it exists in the binary of light-skinned, beautifully sculpted gay men, or larger than life drag queens. I think they're important — it's great, and it's valid, but I can't see myself in it. For transgender girls who can't transition just yet, because of either circumstance or financial situations, I wanted to explore how I could normalise the idea of a trans person being in love. How do I normalise the idea that someone could identify as gay one day, then the next, realise, "Oh I'm not a gay man. I'm a transgender woman"? That was what I wanted to do at first.

But the moment people started turned their interest from the characters to Nick and myself, that's when vulnerability came in. That was the main takeaway for In Love as well.

⁹ Untitled, Ren Hang

2015

In Love confronts the viewers with what a relationship outside of the mandated or socially conforming frameworks can look like in Singapore. Was the local context and the negotiation of it important to you when creating this work?

Queer images are plenty — there are so many of them. But I just wanted to see a brown, transgender girl in love. That's something that's not particularly accessible in Singapore. I'm sure there are artists who talk about such things, but their works are not visible enough.

What I wanted to, initially, was to create a narrative that both included myself and was believable. If other girls like me see In Love, I wanted them to believe that they too could be in love. They didn't have to believe the tragic narratives that surround queer people, specifically brown, queer girls.

But, I'm also fully aware that I'm just starting out. My audience might not be girls like me. I know that people who come across the work will most probably come from the majority. With regards to Singapore, there's always a tension that exists between getting the message across, not compromising its quality, yet still maintaining a certain level of accessibility. I use the word accessible because I'm not interested in acceptance. At all. I don't care if you accept transgender women or not. Queer people come to terms with their queerness at very different stages of their lives. I didn't know I was transgender until I was twenty three. A lot of gay men don't know that they're gay until much later on in life, and it's the same for many bisexual or lesbian women. Women can go through life thinking that they're supposed to like men, until they realise that their entire existence does not rest on a man's acceptance alone. When they begin to unlearn that notion, that's when some women realise their attraction towards women.

So learning the visual language of a majority is important. In a large crowd of people, there probably is a proportion of them who haven't come to terms with who they are just yet. There are also others who would just come by, see the work, and leave. How then, do I create a visual language that can apply to the perceptions of these groups of people?

Being in Singapore, and even at Pink Dot, the idea is just love, love, love, love. I don't think that should be the reason for people to normalise queer existence. Love is everything, but everything is not love. At the end of the day, the human experience boils down to love. But at the same time, why should I only be validated or appreciated just because I deserve the right to love? My queerness isn't just love. It's also my sexuality. It's also my ability to go in and out of different presentations.

There's something very delicate about the way East Asian artists like Momo Okabe, Pixy Yujin Liao or Ren Hang approach "crude" subjects. Ren Hang can take so many pictures of naked people, but there's still a real tenderness present in his images. I'm not sure if it's body language or the quality of light, but there is a certain tenderness. That's something that I wanted to emulate with In Love.

It's also really important that In Love is located in Singapore because of the interracial coupling between Nicolas and I. I didn't really see this at first until others pointed it out. My ethnicity is really important to me. Although this wasn't a relationship, I realised that with love — when it happens, it happens. Some have asked me why my collaborator had to be Chinese. Would it have been any different if a brown person was your partner and collaborator instead? I feel like for In Love, in the context of Singapore, it is through Nicolas that a lot of cis-heterosexual Chinese people are able to see themselves. If Nicolas wasn't a part of this project, it could have been dismissed.

This wasn't something I didn't think of at first. It was during the exhibition itself when there were straight Chinese men coming in, and when they looked at the TV, some of them said that, "You know it's weird, but I see myself in [Nicolas]". It's kind of sad, because it feels as if I'm compromising on my brownness and me being unapologetic in my representation. But still, I feel that it's a conversation worth having. People want to see themselves in the project, and I think by having Nicolas onboard, there was this subconscious mirroring between the viewer and the work. Through this subconscious mirroring, I was actually able to reach more people with what I was trying to talk about — my transgender experience. This probably strays from your question, but it was a point brought up by some people that I didn't personally consider at first.

People definitely project themselves onto the artwork they see. Could you share if you know of how some have, perhaps, reacted or responded to the work in a way that completely misses the point of the project?

Something that's really interesting is also the fact that Nick is a cis-gender, heterosexual man. So, he's straight. I think a lot of people are like, wait — what? So there then begs the conversation of whether it's okay that a heterosexual man is playing a cis-gender gay character. I think it might be problematic to say this, because we're having this wider conversation in the world with Scarlett Johansson trying to play a transgender man, and where transgender actors are trying really hard to get roles. But here I am, enlisting the help of a straight person, to get my queer narrative across.

I think it drives the point of the entire project, and even my entire body of work.

It's not just romantic love, but gender is performed. Sexuality is performed. Ethnicity is performed. There is a certain sense of fluidity that I like to explore in my works, and Nick being a straight person has created another level of dynamic that, I think, drives my message as an artist across.

At the same time, I know this is a problematic and sensitive topic that a lot of queer people felt strongly about. They questioned his motivation as a straight man doing a queer project. I expected that reaction, but I didn't expect the strong extent to which some felt about the situation. It definitely helped create a discussion, and it can help me improve from here on being more conscious about who I then decide to collaborate with.

Speaking about selection, there was also a selection process you took on with curating the sort of objects that would form the exhibition. I was struck by the paper trail, so to speak, of the exhibition — with the photographs and the letters adoring the walls. Why did you decide on found objects or memorabilia as the best medium through which to convey the project's message?

I'm a very nostalgic person, and I feel like a lot of people within my generation share this nostalgia for a simpler past. I mean, I love the Internet and I think the Internet informs so much of the work here. But I also think that there was something really intimate about how we used to print out our photographs and frame them up. Now, everything's on Facebook. That's cool as well, but it's just a completely different experience.

There's an incredibly charming quality about paper. We experienced that shit when we used to write letters before SMS and the Internet. With letters, sometimes you hold off on the emotions that you're feeling. When you write about a week, you could just be writing about the range of emotions that you felt. Whereas with text, you can just tell someone, "Well, I feel like shit today".

The whole idea of love, to me, feels nostalgic. I think having a shared past with another person actually anchors a relationship down, and directs where two people then head towards in the future. Artistically, I wanted to pay homage to the 80's. I love that whole vibe, which is why we have the analogue TV in the space as well.

Another thing I wanted to do was that if older people came to the show, that they would see that, when it comes to love, we actually do have a lot more in common. Even though we now go through mobile phones, they used letters. When they come into the space and see those letters, they can go like, "Oh, I went through this." On the first day of the exhibition, there was this uncle who came into the space. He was a drag queen from the 80's. When he came in, he told me that he went through all of this that the exhibition was exploring. Even though I knew the experience was different, he was trying to explain to me that this looked very familiar to him. So with the presentation of In Love, I had the intention of creating a sense of timelessness — from shooting the photographs on a disposable camera, to printing them out, and then framing them up on the wall.

In order to create the space, I worked closely with Divaagar, who's another queer artist. His work is concerned with queering spaces, basically. So if you have a room, how would you make it look as if a queer person was living in it? He has an upcoming exhibition, Soul Lounge, coming up soon. He visualises it as a space for brown and queer solidarity. With regards to the space for In Love, a lot of the smaller details came about because of Diva's genius brain. There were a lot of happy accidents that happened when we were setting up the space. The bed was kindly donated to us by a couple who live in Sengkang, and I got it off Carousell. The bed was advertised as a single bed, but when I got it, I realised it was a super single. The mattress I had for it was a single one, so I was wondering what to do with the extra space. Diva suggested we could put some photo frames and some cushions there. I didn't really like the idea of the photo frames, so we placed the letters there. Initially, the letters were facing the wall so viewers could squat by the wall to read the letters. It was Diva who then suggested that we could face the letters towards the bed so that viewers could lie down whilst reading the letters.

He worked on two spaces prior to this one, so for him, every single experience the viewer has in the space is important. So with In Love, whilst you're reading the letters, there are sounds in the background. Scent was really an afterthought. Diva mentioned that he had an extra candle at home, and asked if I wanted it. At the same time, I was also influenced by the artist, Zarina Muhammad. Her work involves a lot of research into Southeast Asian legends and folklore. She does a lot of ritual-based performances where she burns incense. I had the opportunity of visiting her home, and she gave me an incense that would protect one against the evil eye. Before the exhibition, I started burning the incense here. That's when I realised that there are different types of scented incense, such as rose incense, that can conjure up images of love. The first few days we burnt red rose incense, and afterwords, Zarina came in and gave me boxes of white rose, yellow rose and purple rose incense. They all have different connotations and meanings. On certain days, one could feel heavier or lighter in spirit depending on the type of incense that was burning in the space.

With regards to the lighting, in the daytime we have natural light coming into the space. But at night, there's only this artificial overhead lights that, I felt, were very flat. It didn't do anything for the experience. So I've actually been watching a lot of videos on the colour of love. Some of these videos talked about how you can actually talk to someone — and I know this is so left field — but these videos associated the colour of orange with the idea of open communication between you and another person. I borrowed lights from school, and included tea lights and fairy lights into the space because they were warm and had an orange tinge to them. The fairy lights also fed into the idea of nostalgia.

A lot of In Love was inspired by the 80's, yes, but I also had indie films from the 2000s in mind. Films like Nick and Norah's Infinite Playlist or 500 Days of Summer. We grew up with those films, so I think it's always been a subconscious desire for me. If I could have a room, I'd really want it to look like it came out of one of those films.

You're working on turning In Love into a zine now, which then brings the paper cycle back full circle. How has the translation process been like between mediums? Do you find that because of how different the two mediums are, that the zine now presents the narrative very differently to the physical space?

With the zine, the choice of paper will be very different because it really changes your experience with it. For the exhibition, I printed out the photographs on glossy paper. I think there's a glamour to gloss. In comparison, matte paper carries a sense of rawness. So I'll probably be printing the zine on matte paper.

The experience [with the zine] is also very curated. When you compare it to the physical space, the viewer can start from anywhere when they come into the room. They can begin clockwise, anti-clockwise, or even on the bed. But with the zine, I'm informing the viewer of how the narrative is ordered exactly. Even with the letters, I'm actually only including Nick's letter in the zine. I'm not even including the letters that we wrote as characters. With the zine, I can present a more simulated reality. When a viewer comes into the exhibition space, it can sometimes seem incredibly staged. The longer one spends within the space, the more one realises how unreal the situation is. However with the zine, you're reading it whilst knowing that there's a story between these two characters that you want to find out more about. The reader doesn't know about how there were characters before this, or anything else about the process. Still, the reader will slowly realise that a couple of the images within the zine are disconnected from each other. Nick's letter gives the reader an objective, unemotional point of view, which I feel, anchors the entire work. My voice is very emotional, and I think that's present in the photographs.

I wanted the zine to be a very condensed version of the work. With an exhibition, you could spend, maybe, half an hour in the space. With the zine, however, I'd probably leave it more open ended. The reader could look at the images over and over again, but with only one letter to inform their perspective, they'll end up having to fill in the spaces themselves. A zine would also be something that would allow more people to access the work.

I also want to share an interesting footnote about accessibility. There was a person who came by to see the show, and told me that he couldn't read the letters. I thought it was the handwriting, which could be quite hard to read. He was like, "No that's not it — I can't read." I think it's a conversation that's worth having in the future, with regards to the artworks we put up. Within this artwork, there's an intersection for the character of nor between being queer and being brown. But beyond this, there are other intersections. Some people are queer and non-able bodied, and if not for the internet, I would have had no idea. Because this viewer brought up the point of him being unable to read — and the letters were such an integral part of the experience — it's something that I now have to think about for future works.

Another problem with this space is that although we're connected to the lift, it's quite some distance away. People who need wheelchairs, or who have babies, would have to go quite a distance just to get here. A lot of us didn't know about this, but I was determined that people should be able to come here regardless. In our vision of inclusiveness for the future, I think we sometimes forget about non-able bodied people, people who can't read, or people who are visually impaired. It's definitely not on the artist to specifically cater to these groups of people, but In Love's message was about inclusion and representation of things that might not necessarily be visible. In this spirit of inclusiveness, I'm thinking about how I can learn from this experience and how I can make my work more accessible in the future. So moving forward, when it comes to my image making, I really want to keep this notion of accessibility in mind for future projects.

In Love is an exhibition at Coda Culture.

The exhibition will run until 21 July 2018.

For more information, visit In Love’s event page.

The exhibition will run until 21 July 2018.

For more information, visit In Love’s event page.