Divaagar is a visual artist whose practice explores the relationships between desires and spaces through installations, space-making and performances. He works at the intersections of bodies, identities and environments, proposing alternative economies and ecologies through engaging with localities, methods of display and re-routing gazes.

The day we meet with Diva for this conversation is an exciting one for the artist. The Straits Times, the leading broadsheet English-language newspaper in Singapore, has just published a full page on the Space Oddities exhibition at the Substation. The excitement is palpable, and you can hear it in his voice — all those years of hard work is paying off. We sit down with the artist over bubble tea to talk about some of the works that have inspired him over the years, and to dive a little deeper into some of his recent works.

The day we meet with Diva for this conversation is an exciting one for the artist. The Straits Times, the leading broadsheet English-language newspaper in Singapore, has just published a full page on the Space Oddities exhibition at the Substation. The excitement is palpable, and you can hear it in his voice — all those years of hard work is paying off. We sit down with the artist over bubble tea to talk about some of the works that have inspired him over the years, and to dive a little deeper into some of his recent works.

¹ Times Square Red Times Square Blue, Samuel R. Delany

Let’s start with the book you picked out, Samuel R. Delany’s Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. It is a book that explores the intersections between urban life and sexuality in a city such as New York. Within that, there seems to be affinities between this book and the ideas you explore within your works. Tell us about your relationship to this text, and how you’ve seen its ideas seep into or frame your practice.

The city is built upon the reactions and experiences of a multitude of people, and it is important to understand how different groups of people shape the city.

The book also goes into what happens to spaces when they undergo gentrification. Personally, I find it incredibly interesting to understand the city through its architecture as well. For me, what I find most significant about this book is how it views the city as a space where things happen.

In this book, Delany combines his own personal experiences of passing through the city along with more academic theorisings about the city, its spaces and their potential. Studies into an urban landscape are often data-driven, and academics who engage in this sort of work often take on the voice of a distant observer. In combining the personal with the scholarly, Delany created a richness about his writing that is lacking in more scholarly essays about urban life and urban geography. Did this mode of synergistic thinking appeal to you whilst reading this book?

For me, this touches on a bigger problem inherent to academia itself, particularly its ability to detach itself from the very thing it studies. For Delany, a city has to be examined through the lens of those who inhabit it. This is something I do with my own works as well. Places are built, but the communities that live there contribute to a continuous process of place making as well. When we examine how different cultures relate to space, there are meanings that are ascribed to certain places, and there spaces that take on new meanings depending on who moves through it.

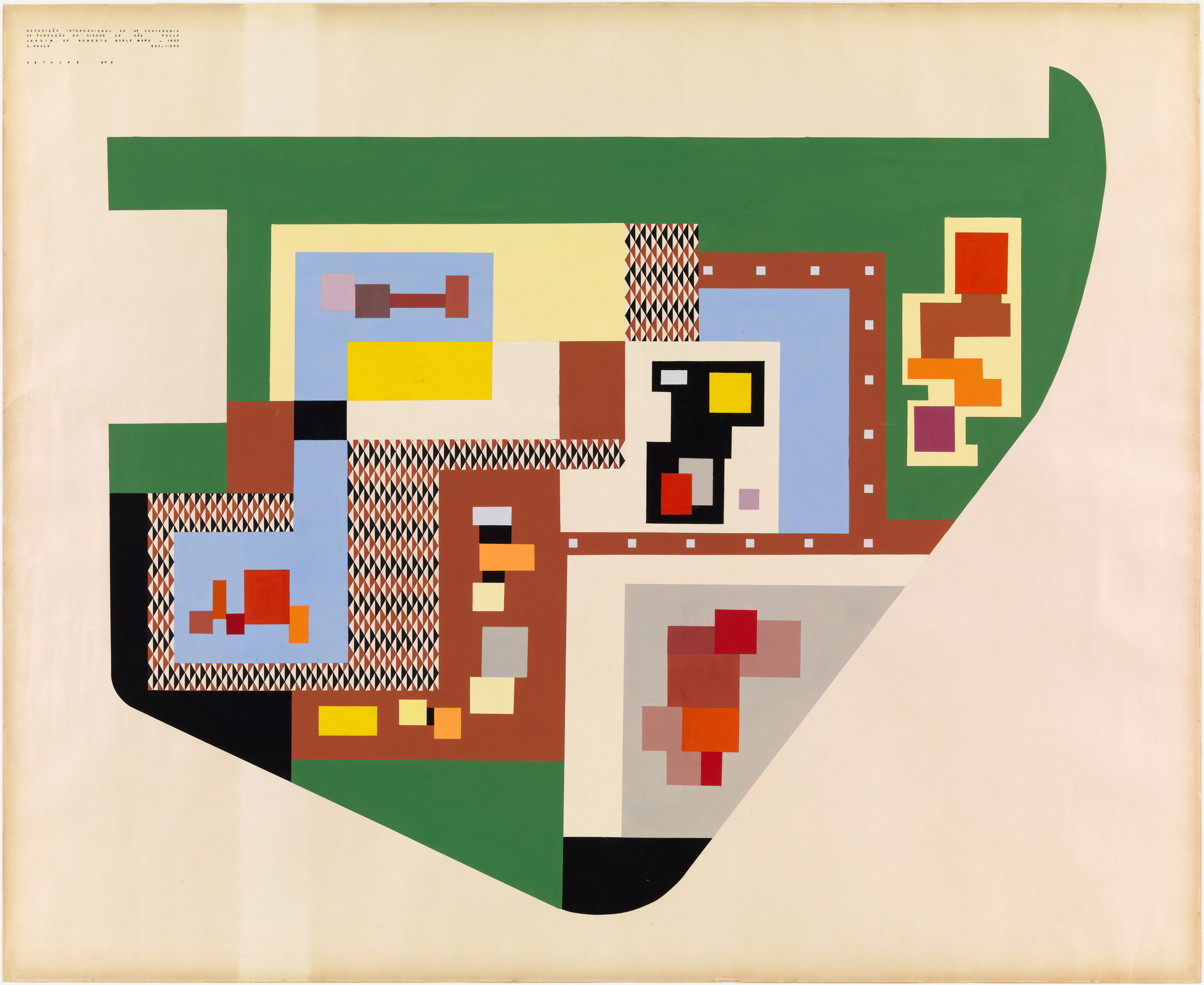

² Ibirapuera Park, Quadricentennial Gardens, project, São Paulo, Brazil, Roberto Burle Marx

The Museum of Modern Art, 1953

This would be a good point at which to talk about how you work with spaces, and how that came to be. Another work you picked out for our conversation is a plan by Roberto Burle Marx. He worked primarily as a landscape architect, but approached it as a three-dimensional art form. How did you come to work with spaces, and what intrigues you about the latent potential within working with physical, emotional and metaphysical spaces?

Prior to working with spaces, I worked in mediums that were mostly two-dimensional. I painted and I did embroidery. I never really thought of spaces as a possible medium for art until I started working as a gallery sitter. I worked as a gallery sitter for close to three and a half years. There is something amazing about seeing exhibitions go up and come down. An exhibition’s design is always sensitive to or caters to the artworks on display. During my time at the gallery, I started to see how much of a distinction we place between the exhibition itself and its design. I wanted to fuse or use the elements of set and interior design to frame how art could be experienced. I wanted to think more deeply about an audience’s experiences within a space as well, so that’s how I started working with space.

Looking back to Burle Marx, I only came across his work sometime last year when I became very interested in plants. His name came up in my research because there are some plants that have been named after him. I found his work very interesting because it sat at the intersections of design, landscape and art. The philosophies that drive his designs are also very human-centric. He would pose himself questions such as, “What would visitors feel when they pass through this park?” His works were framed with the viewer’s experience in mind. That got me reflecting on the potential of using dividers and objects in a space, and how that frames the space as well.

Something that struck me with Singapore is for lovers was how you carved out small corners and private spaces. The work presents a speculative scenario where sexuality can be exercised without surveillance and curtailing. Yet throughout the space, you use curtains and walls of plants to conceal and obscure. Within an exploration of permissiveness, why did you decide to hide certain areas from the viewer’s line of sight?

For me, I wanted to think about how it would be like if we could ascribe some comfort to these spaces. Most of these spaces aren’t very nice. To cruisers, these spots are hidden gems. What would it look like if we thought of these sites in relation to luxury and comfort?

That was really my intention behind it.

To think about what it means to highlight these issues through half-obscured spaces and secret corners, I’m not really sure how to answer that question. It’s one of those things that you could choose to address or not address. Either way, the space becomes implicated.

³ Singapore is for lovers, Divaagar

2019, Installation View at the Substation

Photography: The Substation

2019, Installation View at the Substation

Photography: The Substation

Often when people think about an unfettered or unmanaged space, we can approach it in a very binarist manner. A space without surveillance should be devoid of segregation. It should be completely free and completely open. Yet coming into the space, there is this sense of covertness and secrecy embedded into it. It leads viewers to the notion that maybe sometimes, the point of an artwork is to know that you don’t know everything about it.

It is very much about that too. Thinking about these activities as a form of resistance as well, I think Singapore exemplifies a particular sort of duality. The state knows you’re doing it, but they close one eye to it. For me, it is very obvious that these things are happening in certain spaces. This work was me processing this by then putting these activities on full display.

⁴ Domestic Integrities Part A01: New York, Fritz Haeg

2012, Installation View at The Museum of Modern Art

Coming to your choice of Fritz Haeg’s work Domestic Integrities, there are clear parallels between the organic nature of Haeg’s work and the works you create as well. Are there particular elements of this work that you find compelling?

I picked out Domestic Integrities because there was a period of time in my practice where I was looking into alternative domesticities. I came across this work, and it got me thinking about how a communal activity can function as the spark towards creating discourse, affinities and further action. I really enjoyed how the participants would really just sit down to create and knit a rug together. There was this fostering of a sense of community.

Although these created communities and affinities can be said to be temporary in nature, it still resonates a lot with me and my practise. I think there is a temporality around almost everything I’ve done. If we’re talking about the exhibition format, these relationships and bonds are first built within a space. But when the exhibition is dismantled, they move on into inhabiting other spaces. It’s reflective of an experience like knitting a rug together. For me, it’s more about the idea of a communal performance as well. As an artist, you can’t really control what someone takes from a work. One thing you can be sure of is that there is always going to be a ripple effect, be it artistically or how individual viewers remember their experiences in the space.

Some artists enjoy the process of being able to be very present in their work — in creating the work, displaying the work, and framing how it will be understood. You often work with things that are unpredictable — organic matter such as plants, and communities where every individual brings something different to the table. How do you approach creating such works, especially since the work tends to take on a shape or form outside of yourself as an artist?

Whether I’m given a space or I pick a space to work within, I always start off by envisioning how the work will look like in it. For me, everything starts from the floor plan. This can sound very different to the themes that I usually work with, be it the collaborative aspects of organic matter or the performances. There are certain things that you can put into a framework, and so there is still a level of control. But when we speak of unpredictability, I would say that comes in most clearly when it is time to let go of a work. Certain things can only shape within an exhibition.

Of course there have been instances where I’ve imagined spaces, and it didn’t worked out quite the way I wanted it to. I don’t just write these instances off as bad experiences. There’s always room to grow in learning from the spaces and the installations that I’ve made. You can always rethink how things are framed, how we demarcate spaces, and how we perform. There’s so much to be learnt from failure as well. Things don’t always work out the way you planned, but I think one’s intentions can always be read.

⁵ Singapore is for lovers, Divaagar

2019, Installation View at the Substation

Photography: The Substation

2019, Installation View at the Substation

Photography: The Substation

⁶ Scales, Solange Knowles

2017, Performance at Menil Collection

⁷ Drama Queens, Elmgreen & Dragset

2007, Installation View at Skulptur Projekt Münster (Allemagne)

Let’s talk about the two other performance works you picked out for our conversation. Solange Knowles’ SCALES and Elmgreen & Dragset’s Drama Queens are very different works, yet they have both been described as performance. Performance is often tricky to define because there are so many ways in which a performance work can be made. What does performance mean to you, and what does it mean to create a performative work?

Performance, or this idea of performance, is evident in a lot of things, even things outside of the art sphere. You can even see this in terms of how laws are enacted. In the context of Singapore, we have harsh drug laws to maintain this image of a clean and strict nation. On the other hand, we have 377A — a law that remains in the penal code, but is not actively enforced. We perform this notion of being a progressive nation whilst trying to appease conservative pockets within the country at the same time. I observe performance on every level of society and daily life, so it’s hard to pinpoint what exactly it means to me. Earlier, I spoke about frameworks and how certain rules and expectations demarcate spaces. When we think of how visual signifiers work, that’s just another way in which people perform within spaces. These are just some of the performative elements that I employ within my work.

To be honest, I’m not much of a performer myself.

Sometimes, the body is a very necessary presence. But other times, the body can be performed through images of people or through objects.

The performative nature of things is actually more important to me than the performance aspect of myself.

This is really interesting because what you’re saying is that things, inherent to themselves, are able to perform, depending on the context you place them in.

Especially with things such as installations, there are certain objects placed in particular spaces to signify how these spaces are meant to be used or occupied. These objects are often utilitarian in nature.

Thinking deeper about this, the histories of certain spaces can be performed as well. There’s an element of performance embedded into how we highlight certain aspects of a place’s history over others. With art, you do find elements of performance beyond the work itself. Through exhibition or wall text, for example, we are consciously building worlds within works.

Since you touched on the idea of performing histories, let’s talk about the work you did at A Weekend Affair. Academic discourse has done a lot of work, albeit mostly from the perspective of a distant observer, on how we’ve privileged certain narratives throughout the course of history. There has been a lot of discussion around the importance of decolonising thought, but what you did through The Hibiscus: Spa & Wellness touched on something that academic discourse can only hint at — the decolonisation of the body. Why did you decide on taking the physical body as your point of departure, and how did you conceptualise the work?

Going into this year of 2019, we see the Bicentennial turning into such a spectacle. If we’ve learned anything from Guy Debord, it is that the spectacle can become an all consuming thing in and of itself. A Weekend Affair was conceptualised as a countercultural movement, but in some ways, it added to the spectacle of the Bicentennial as well. It brings us back to the point I made earlier. You can either point very clearly towards something, or you can ignore the elephant in the room. The whole purpose of The Hibiscus: Spa & Wellness was to distract people from the Affair itself. It is through this distraction, being put through the experience of a massage or a facial, that one is kept separate or detached from the event. Primarily, the work created a separate space within the entire event.

At the same time, I also wanted to play around with the way in which the Affair was advertised. I wanted to use the textual tropes that are associated with massage parlours or wellness centres. Many of these places emphasise their use of natural remedies or traditional methods. I used these terms when talking about The Hibiscus as well, but not in the way one would imagine them being used. When I speak of natural remedies, I’m referring to Vicks VapoRub. This is something that has been used in my family for several generations, but wouldn’t immediately come to mind when one hears the term “natural remedies”.

Finally I invited two artists, Alysha Rahmat Shah and Zeha H., to perform this piece. I specifically asked Malay, Indian or brown-skinned artists to be a part of this work so as to further emphasise the fact that this was a performance of nativity, with indigenous people performing these services. It gave the work a facade of authenticity. There was also a lot of code switching that happened during the performance. Throughout the performance, Alysha and Zeha would switch between speaking in English and Malay. I was very inspired by white ladies going to Vietnamese nail spas, and thinking that the manicurists were bitching about them in Vietnamese.

⁸ The Hibiscus: Spa & Wellness, Divaagar

2019, Installation View at A Weekend Affair

2019, Installation View at A Weekend Affair

How did the participants respond to the work?

It sounds like The Hibiscus: Spa & Wellness functioned almost like a decompression space of sorts. Was this intentional in that both you and the organisers felt that such a space would be important to have; or did it happen more organically in that personally, you felt that it would be interesting to create this space within the Affair?

When I first pitched this idea to the organisers, it wasn’t revealed fully to them what the work was. I wanted to keep it from being sensationalised as a work that particularly deals with the spectacle head on. I wanted it to seem like any other spa retreat, so that people could figure out what the experience meant to them on their own terms. Particularly with performance, I think that there has to be an element of surprise and levels of subversion. If you reveal everything to participants from the get go, then the magic of the performance is dissolved.

People like a good tease. In some ways, performance is almost a wooing of the audience. In order for the work to really come into itself, the audience has to reciprocate as well.

This touches on a larger problem that I see with artists who engage with more bodily works of performance. It is often very confrontational. If we’re thinking about performance in the way that it is staged, the presence can be quite intimidating. Other than the fact that the spectacle of the work is the performance itself, it doesn’t quite invite people to look closely or sit with the work. This is something I’ve observed, and it is something that keeps me away a little bit from performance as a category.

The presence in a performance work, when overly confronting, can be unproductive. It’s a bit of a cliché, but medicine does taste better with a spoonful of sugar.

⁹ The Hibiscus: Spa & Wellness, Divaagar

2019, Installation View at A Weekend Affair

2019, Installation View at A Weekend Affair

An earlier work you did at soft/WALL/studs, The Soul Lounge, was interesting in that the installation space functioned as a space for communities to come together, discuss and create networks in a way that other physical spaces might not have been equipped to facilitate. However because it was a temporal installation, the work had to be taken down and dismantled. Obviously things do not have to remain attached to a physical space, but having a spatial marker can help. In the absence of that, how have you seen the discussions germinated at The Soul Lounge sprout or manifest in other ways?

A lot of different things and ideas have manifest from The Soul Lounge. I’m thinking in particular about the performance nor, Zeha H. and Atiq did, Bujang *apok. It has since seen its own reiterations elsewhere, and a new iteration is in the works as well. For me to see how the spark of one collaboration that happened within the space is taking on its own life is so inspiring. I can’t really even say that I’m surprised. I just want to say that I’m really proud of the three of them.

I don’t think things really need to be physically formed as the first iteration of The Soul Lounge was. I don’t see such projects as permanent fixtures because it was a very unsustainable business model to begin with anyway. It also came with its own problems as well. You’d have people who the space was not catered toward come in, and expect to be treated like they usually are. When they are not, they then go on to write scathing reviews of the space online. It’s quite taxing on me to have to deal with that sort of reaction.

There is always plenty of space to rethink, reform and restructure the way projects take hold, but I don’t really believe in the permanence of performative installations like this. I think they are better off as temporal entities. As artists, we play to the spectacle of exhibitions and events as well. Something like The Soul Lounge could only exist within a certain timeframe. It could never really be a permanent monument or incubator.

Unless it is completely necessary, there is also no point in doing the same thing twice. Certain things come and go to make a point. I’m not here to build monuments or to build a complete and coherent stand on certain issues. I don’t want to think about my work as reactionary, but I do respond or react to how things are at a certain point in time. Artworks, if we’re thinking about how we make them, have to stay true to the times as well.

¹⁰ The Soul Lounge, Divaagar

2017 - 2018

2017 - 2018

Throughout your works and the installations you create, there seems to be an emphasis on ideas of intimacy and fostering discussion or care in spaces. Why are these spaces important for you to create?

Everything I do stems from my own desire to seek comfort within spaces. It really never started out as intentional, but identifying the spaces I create with a notion of intimacy became really important to me. We do seek affinities with the spaces we interact with, so a sense of comfort really helps. Tactile objects really help create this environment. For example if you’re trying to replicate the comforts associated to home or a domestic environment, there are certain textures that would complement that idea. These objects aren’t wholly responsible for creating an intimate space, but they do help in enticing viewers towards approaching a space. I think that’s important when you’re trying to establish some kind of discussion or conversation around whatever your subject might be.

When we talk about facilitating discussion or creating spaces of care, it is important to feel as if one is at ease within the spaces. Intimacy effectively helps these conversations along. If you were to compare having a conversation in a classroom to having a conversation at home, it becomes clear that the environment matters. One needs to feel comfortable in order to talk or open up. The environment one is in becomes a trigger or even a starting point for a wider conversation.

Space Oddities is now open.

The exhibition will run at The Substation until 4 August 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.

The exhibition will run at The Substation until 4 August 2019.

More information about the exhibition can be found here.